Call:

glm(formula = vote02 ~ treatment, family = "binomial", data = GOTV)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 0.184717 0.003306 55.870 <0.0000000000000002 ***

treatmenttreatment 0.170824 0.018843 9.066 <0.0000000000000002 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 524839 on 381061 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 524756 on 381060 degrees of freedom

AIC: 524760

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 3Data Science for Business Applications

Causal Conclusion

If we run a regression predicting \(Y\) from \(X\) and find that \(X\) is a significant predictor of \(Y\), we would like to conclude that \(X\) causes \(Y\). But it might be the case that:

\(Y\) actually causes \(X\).

\(X\) and \(Y\) are not actually related in the population; they happen to be correlated in the sample just by chance.

A common variable \(Z\) (a confounder) causes both \(X\) and \(Y\).

A common variable \(W\) (a collider) is caused by both \(X\) and \(Y\).

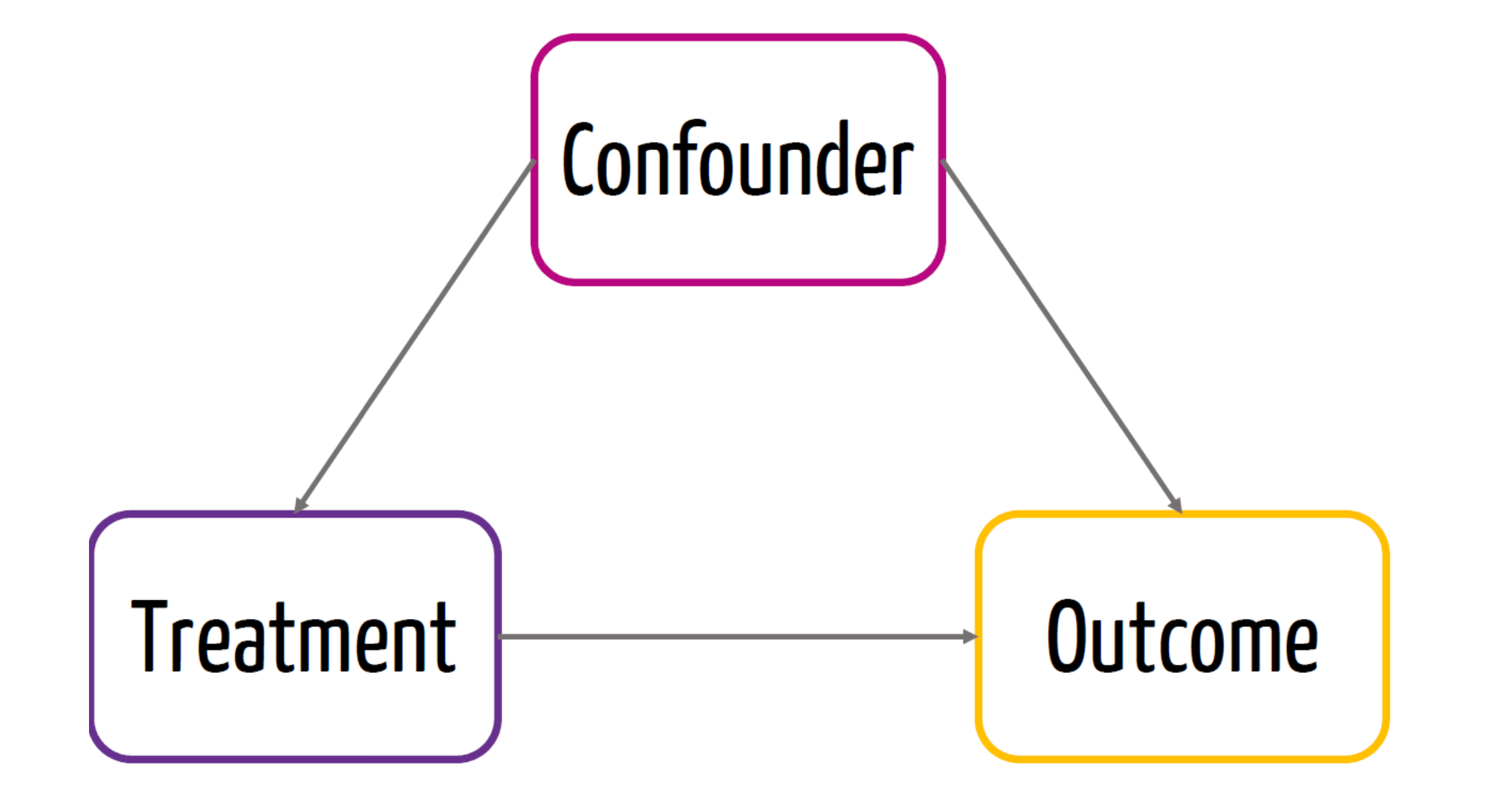

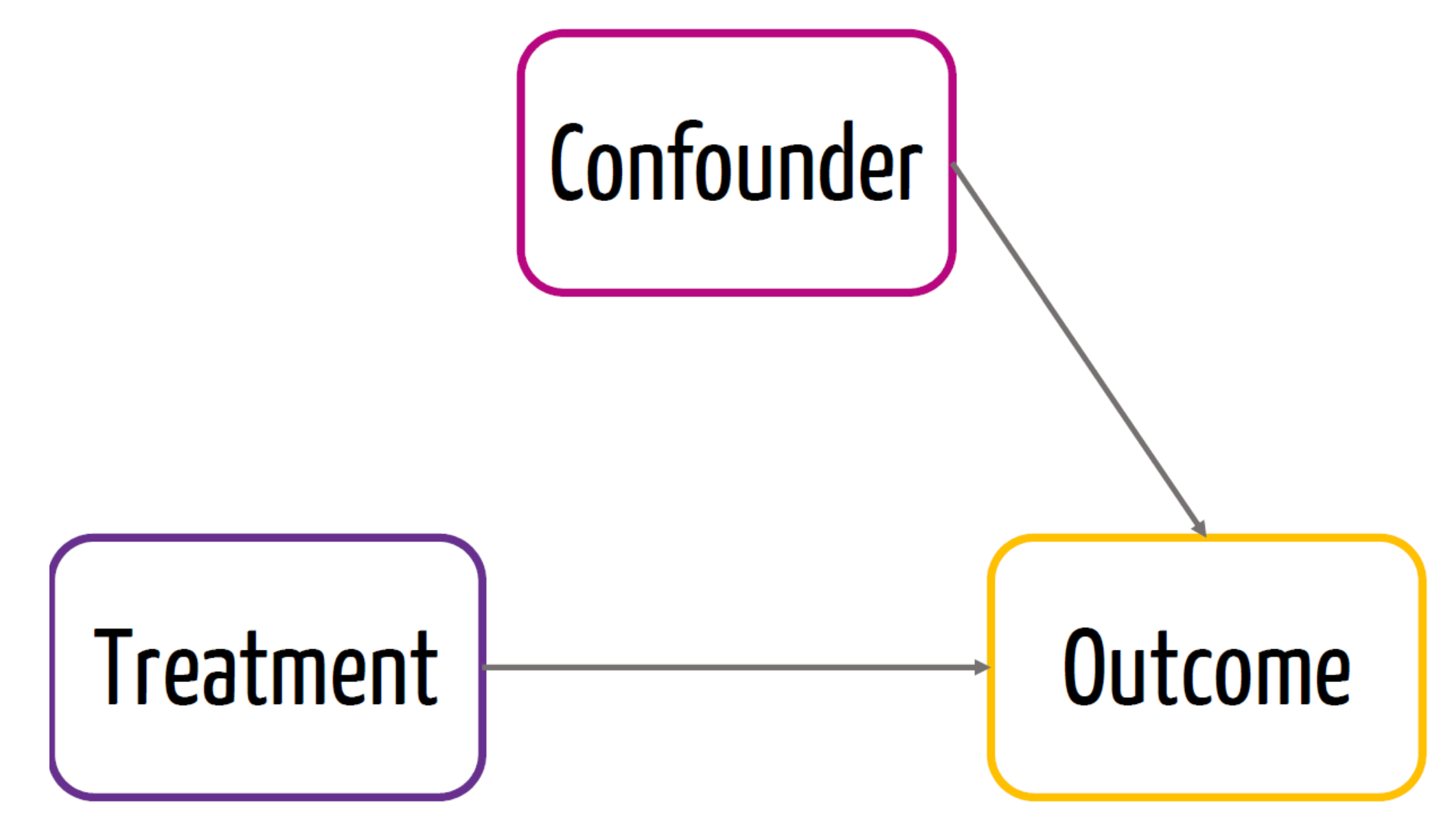

Confounders and Colliders

A confounder is a third variable that causes both \(X\) and \(Y\) and explains the observed correlation between X and Y.

A collider is a third variable that is caused by both \(X\) and \(Y\).

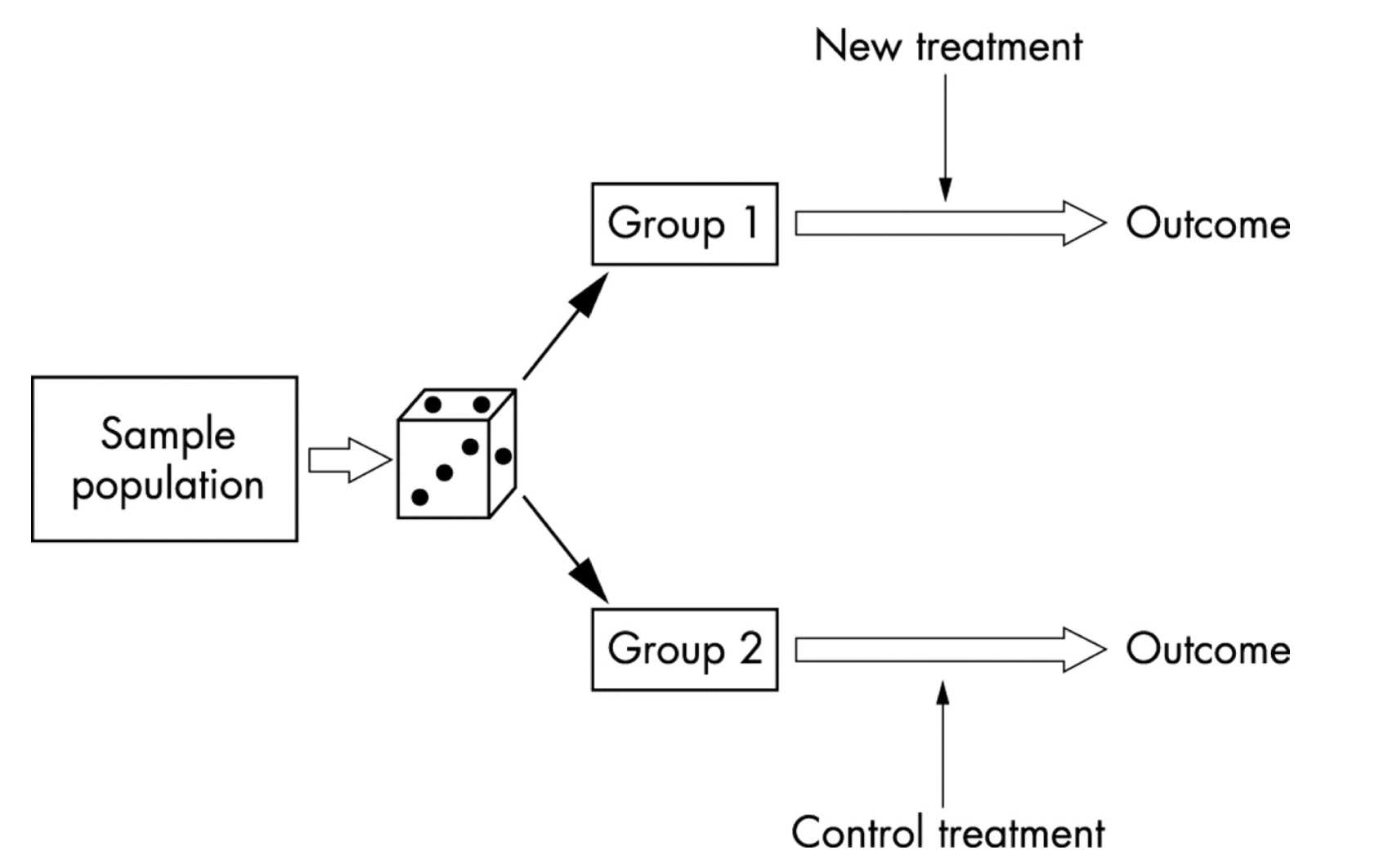

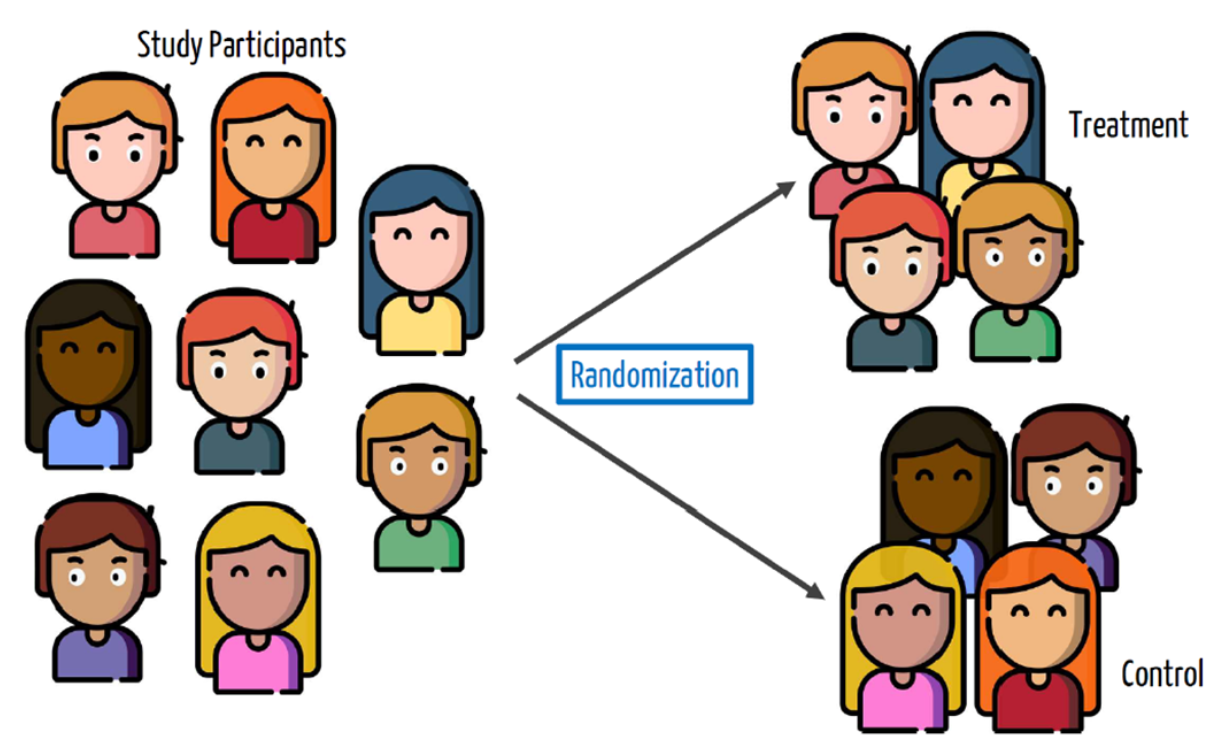

Randomization

One way to make sure the causal conclusion holds is to do it by design:

Randomize the assignment of the treatment \(Z\)

i.e. Some units will randomly be chosen to be in the treatment group and others to be in the control group.

What does randomization buy us?

Control for unforeseen factors (confounders)

Confounders

- Confounder is a variable that affects both the treatment and the outcome

Randomization

- Due to randomization, we know that the treatment is not affected by a confounder

- This would be the causal effect of the treatment

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Often called the gold standard for establishing causality.

Randomly assign the \(X\), treatment, to participants

Now, any observed relationship between \(X\) and \(Y\) must be due to \(X\), since the only reason an individual had a particular value of \(X\) was the random assignment.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

RCT - Steps

Randomize

Check for balance - (balance between the treated and untreated)

Calculate difference in sample means between treatment and control group

Problem with causal inference

- Suppose you have a headache, and you take an asprin. Then you don’t have a headache. Did the asprin work?

| Person | Took aspirin | Didn’t take aspirin |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | no headache | ? |

| 2 | no headache | ? |

| 3 | no headache | ? |

| 4 | no headache | ? |

| 5 | ? | no headache |

| 6 | ? | headache |

| 7 | ? | headache |

| 8 | ? | headache |

- For any given person, we can only observe one outcome or the other, depending on whether the person took an asprin or not:

Problem with causal inference

The best we can do is compute an average treatment effect (ATE): the difference in the proportion of the treatment vs control group \[ \begin{aligned} \text{ATE} &= (\% \text{ headache among aspirin–takers}) \\ &\;\;-\; (\% \text{ headache among non–aspirin–takers}) \\ &= \frac{0}{4} - \frac{3}{4} \\ &= -0.75 \end{aligned} \]

Headaches decreased in 75% among those who took aspirin compared to those who didn’t take aspirin.

We can only make this conclusion if the treatment was randomly assigned.

Example 1: Vaccine Trial

Phase 3 Clinical Trial for the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine

\(X\) = got the vaccine, \(Y\) = got COVID-19

Randomly assign study participants to get either the vaccine (an treatment group of 14,134 people) or a placebo (a control group of 14,073 people)

11 vaccine recipients got COVID; 185 of placebo recipients got COVID

Issues with RCT

- Internal validity is the ability of an experiment to establish cause-and-effect of the treatment within the sample studied.

- Examples of threats to internal validity:

- Failure to randomize.

- Failure to follow the treatment protocol/attrition.

- Small sample sizes

Issues with RCT

- External validity is the ability of an experimental result to generalize to a larger context or population.

- Examples of threats to external validity:

- Non representative samples.

- Non representative protocol/policy.

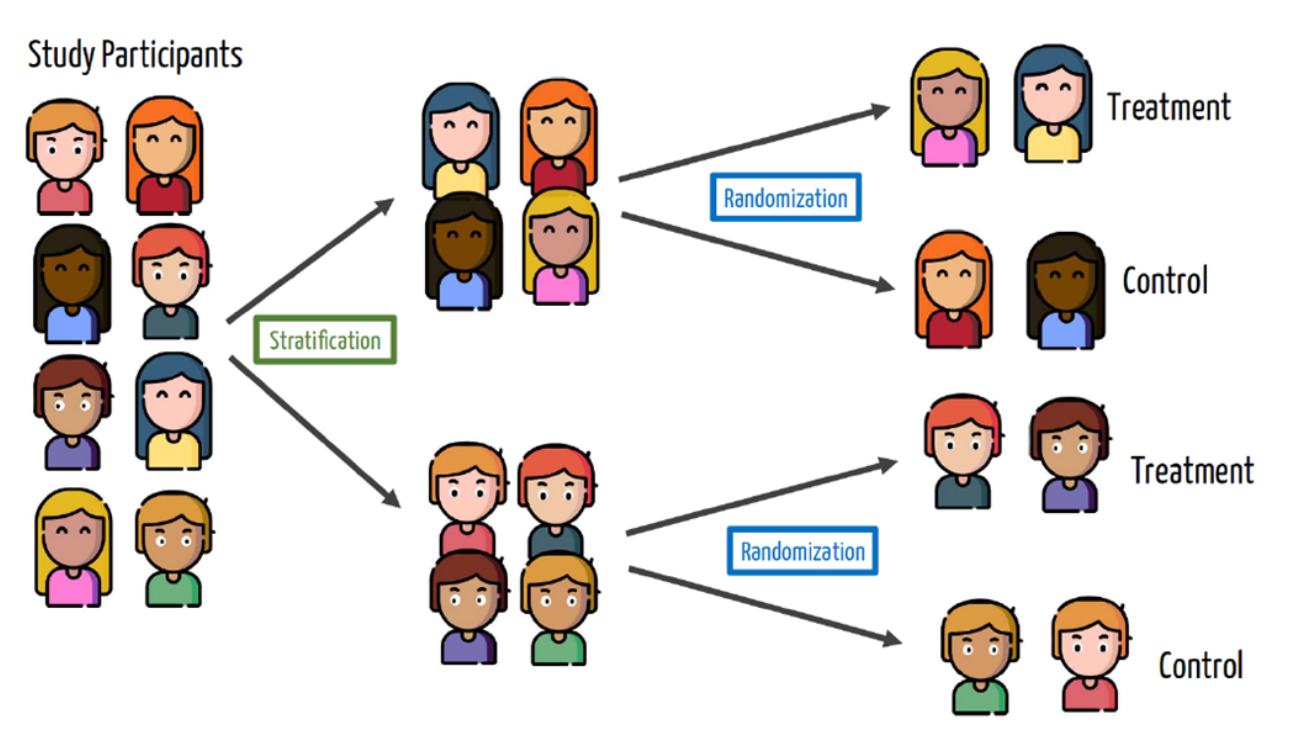

Blocking

Randomization works on average but we only get one opportunity at creating treatment and control groups, and there might be imbalances in nuisance variables that could affect the outcome.

For example, what will happen if the treatment group for the Moderna trial happens to get younger people in it than the control group?

We can solve this by blocking or stratifying: randomly assigning to treatment/control within groups.

Blocking

- Unbalanced sample - Males and Females

Blocking

- Blocking or stratification sample

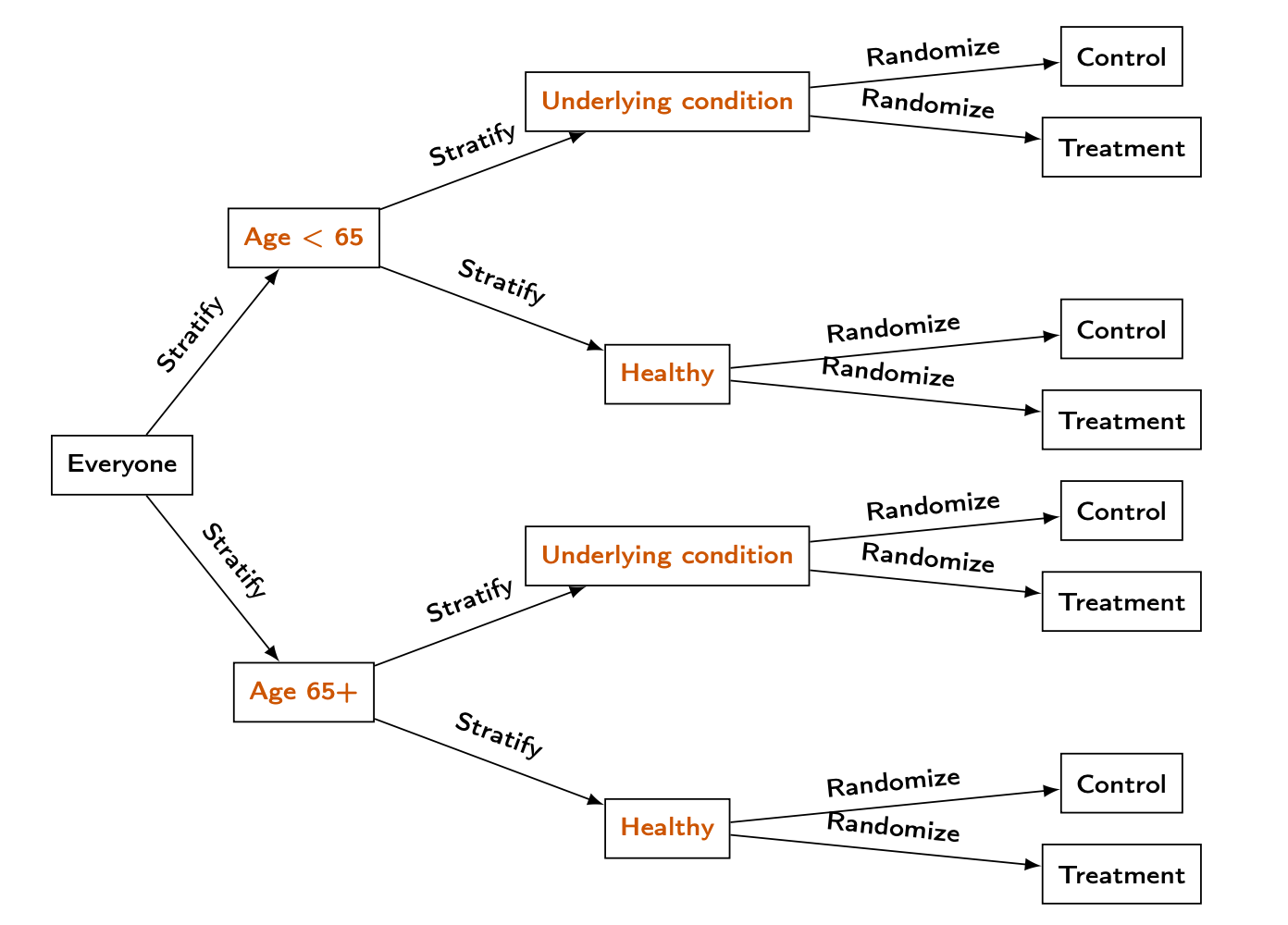

Blocking in vaccine trial

In the Moderna vaccine trial, they identified two possible variables that could impact COVID outcomes:

Age (65+ vs under 65)

Underlying health condition

Blocking in vaccine trial

Experiments using regression

Non-blocked design: use a simple regression \[ \widehat{Y} = \widehat{\beta}_0 + \widehat{\beta}_1 T, \]

where \(T\) is a dummy variable that is \[ T = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{for the treatment group}, \\ 0, & \text{for the control group} \end{cases} \]

\(\widehat{\beta}_1\) represents the estimated average treatment effect. The regression needs to be logistic if \(Y\) is categorical!

Experiments using regression

- Blocked design: use a regression that controls for the blocking variable \(B\):

\[ \widehat{Y} = \widehat{\beta}_0 + \widehat{\beta}_1 T + \widehat{\beta}_2 B, \] where \(B\) is the fixed effect of each strata, that are interactions between categories.

- Important: the regression needs to be logistic if \(Y\) is categorical.

Get Out The Vote (GOTV)

In 2002, researchers at Temple and Yale conducted a large phone banking experiment to see calling voters helps:

From among about 381,062 phone numbers of voters in Iowa and Michigan they randomly contacted about 12000 voters

The outcome Y of interest is whether each voter actually voted.

No blocking

Estimating the average treatment effect with logistic regression:

- The coefficients are in log odds.

No blocking

- The average treatment effect will be of approximately 19%

[1] 18.53049 2.5 % 97.5 %

(Intercept) 0.1782378 0.1911978

treatmenttreatment 0.1339278 0.2077954Receiving a phone call increases the likelihood of voting by 19% compared to those who did not receive a call.

Confidence interval for the treatment

Blocking

The researchers actually used a blocking design with two variables that they thought could impact voting rates (separately from the phone calls):

The state of the voter (Iowa or Michigan)

Whether the voter was in a “competitive” district (one where there was likely to be a close election)

Blocking

Blocking

GOTV = GOTV %>%

mutate(block = interaction(state, competiv))

glm_vote = glm(vote02 ~ treatment + block, data = GOTV, family = 'binomial')

summary(glm_vote)

Call:

glm(formula = vote02 ~ treatment + block, family = "binomial",

data = GOTV)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 0.043236 0.004146 10.43 <0.0000000000000002 ***

treatmenttreatment 0.028542 0.019279 1.48 0.139

block1.1 0.351686 0.015168 23.19 <0.0000000000000002 ***

block0.2 0.196691 0.008866 22.18 <0.0000000000000002 ***

block1.2 0.603739 0.009515 63.45 <0.0000000000000002 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 524839 on 381061 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 520331 on 381057 degrees of freedom

AIC: 520341

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Blocking

The effect of the treatment is not significant.

What if some callers didn’t stick to the script?

Many people didn’t answer the phone!

What about voters outside of the Midwest?

The limitations of RCTs

Although powerful for inferring causation, RCTs are difficult to apply.

They can be incredibly expensive.

Compliance with the treatment protocol isn’t perfect (e.g., mask-wearing, picking up the phone)

It can be hard to generalize beyond the participants involved in the study.

They can be impractical or (e.g., effect of education on performance) or unethical to conduct (e.g., seatbelts, parachutes, even medical trials)