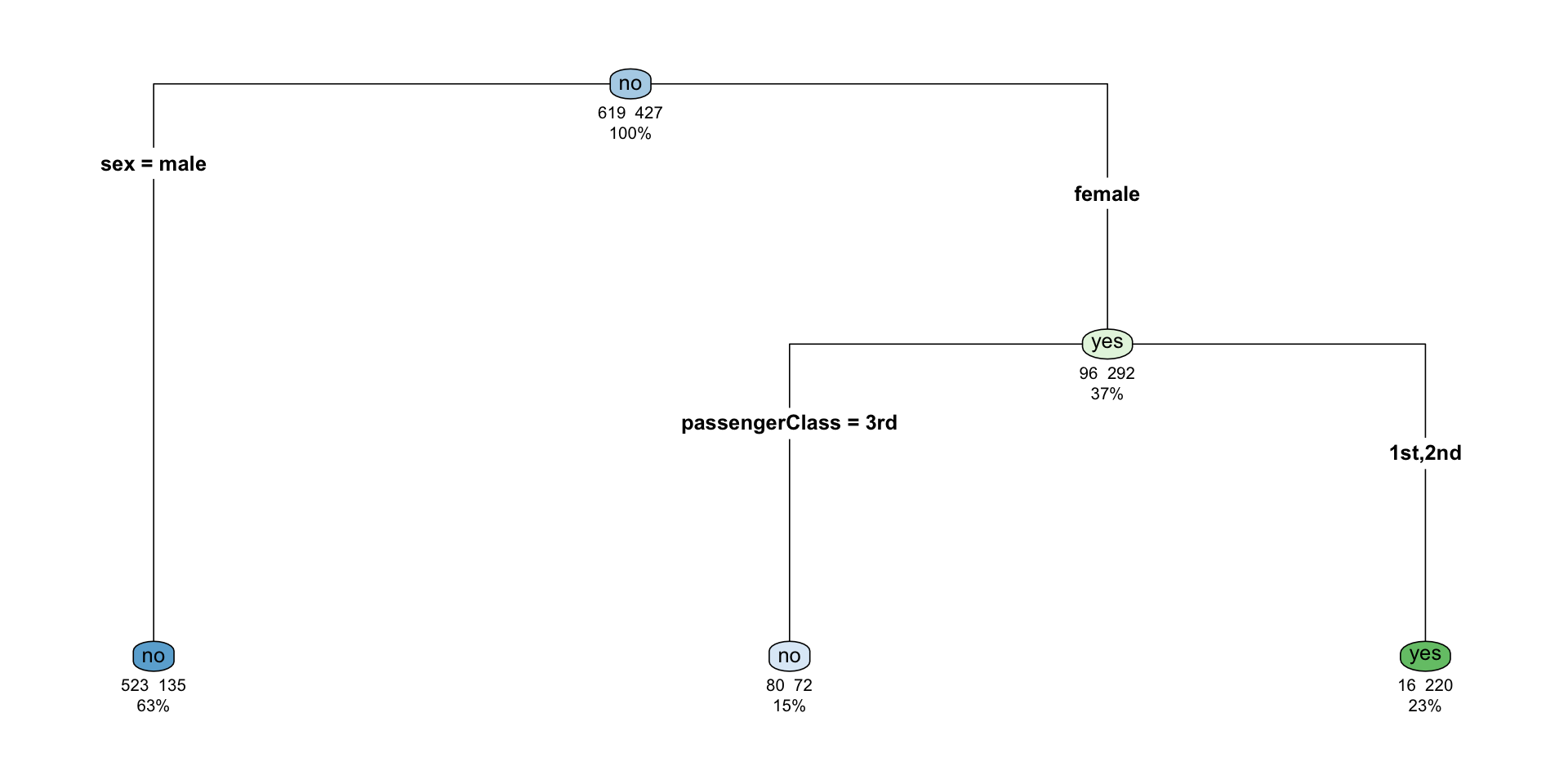

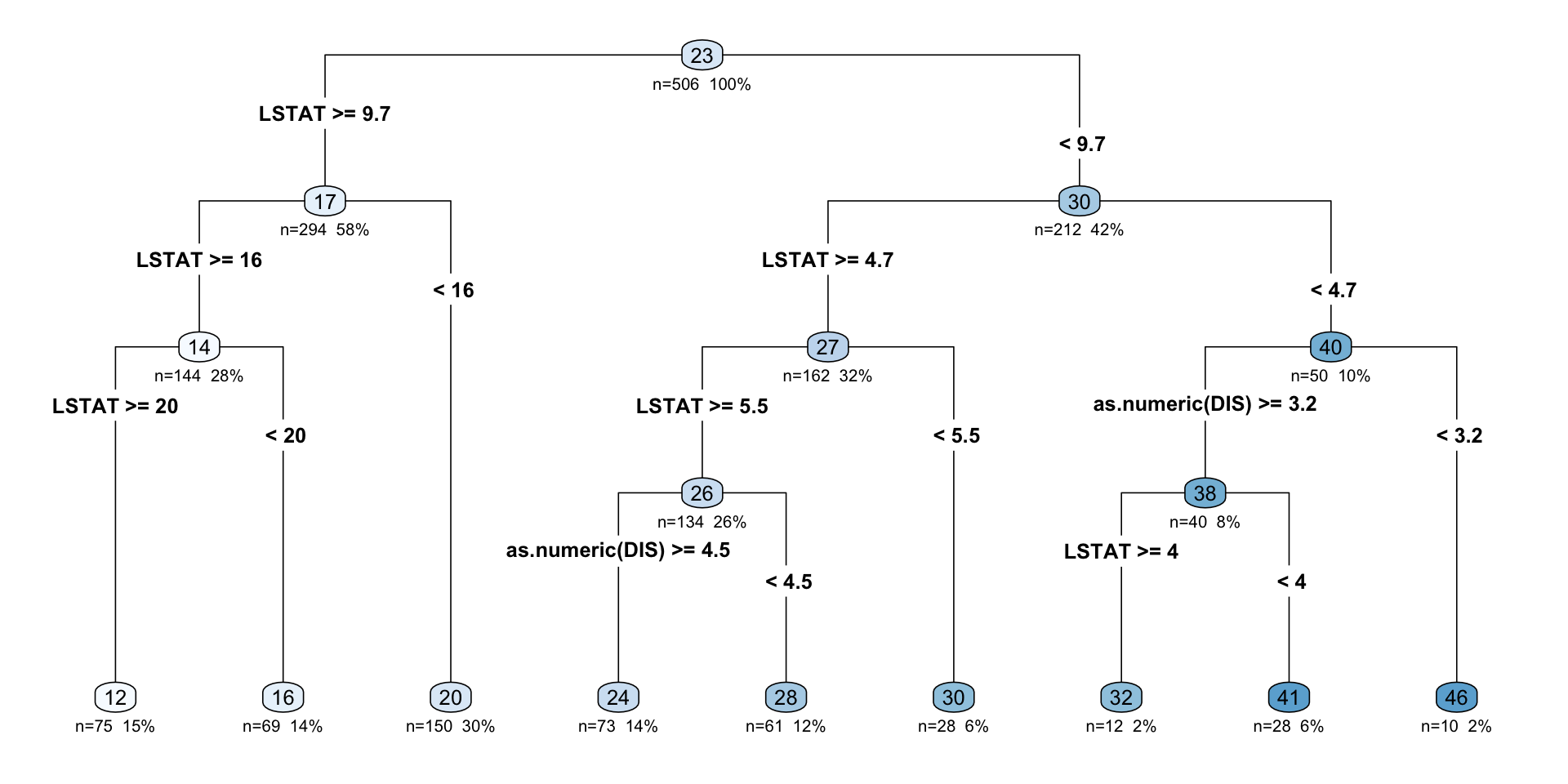

The nodes indicates which group of the target variable is more common in the split. If it indicates no it means that there’s a higher chance of not surviving than surviving.

So in the top node we have no and it indicates that from a total of 1046 (100%), 619 survived, and 427 did not.

We then use the first decision rule that splits the data into gender. It indicates that 63% (658) of the passengers are male and 37% (388) female. From those who are male, 523 died and 135 survived; that is 135/658 = 0.21, or 21%. In this case 523/658 = 0.79, or 79%, died. That’s the reason the node is no on the node.

From the 388 females, 152 were in the 3rd class, from which 80/152 = 0.53, or 53%, died, and 72/152 = 0.47, or 47%, survived. Of the female passengers in the 3rd class, 16/236 = 0.067, or 6.7%, died, and 220/236 = 0.93, or 93%, survived. In this case we can see that the node indicates an yes.

Overall the female node indicates that 96/388 = 24% of the female passengers died and 292/388 = 75% survived.